Ted Grimsrud—April 29, 2018

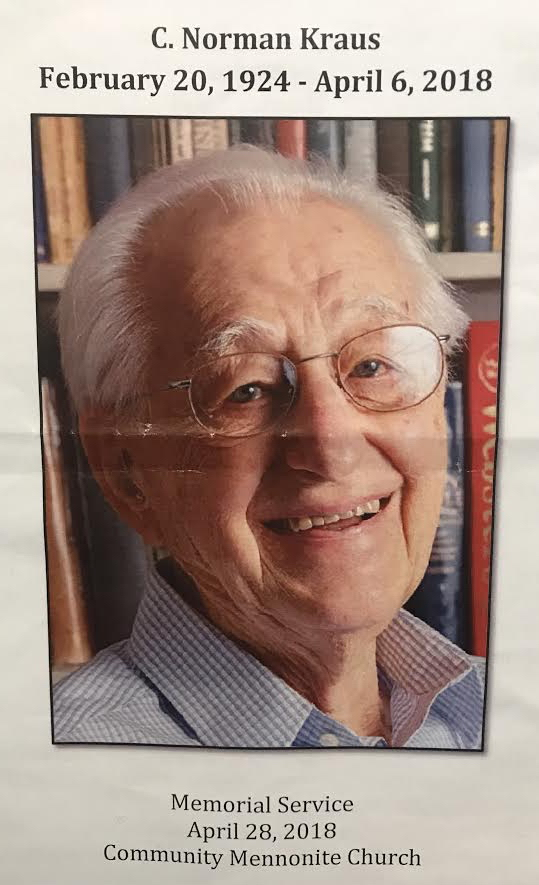

As I appreciatively joined in the memorial service yesterday (April 28) for my friend Norman Kraus, who died on April 6 at the age of 94, I reflected on my first encounter with his writing. Back in the Spring of 1976, if I had imagined that 42 years later I would be sitting in a Mennonite church in Virginia grieving the loss of the author of The Community of the Spirit as one who had been my good friend for over 20 years I would have been pretty shocked.

My final term attending the University of Oregon, Spring 1976, was when I decided not to pursue journalism as a career. I went ahead and graduated that term, but with no intent to stay with journalism. I had gotten intensely involved in a small evangelical congregation, gotten bitten by the theology bug, and read with great attention writings by Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Jacques Ellul among others.

I took to browsing the shelves at Northwest Christian College, next door to the UO, looking for books to help me deepen my theological understanding. I happened upon a small volume written by a man named C. Norman Kraus who was identified as a Mennonite professor at a college in Indiana. Not only did the name Goshen College mean nothing to me, the term Mennonite also meant nothing to me.

However, when I started looking at the book, I quickly was hooked. Kraus spoke a language I understood—”discipleship,” “community,” “the gospel of peace.” I read the book thoroughly a couple of times and began to look for other Mennonite writings. That lead to Guy Hershberger, John Howard Yoder, and Millard Lind. It also led us to going to hear Myron Augsburger when my wife Kathleen and I visited her family in Arizona. One thing led to another, we visited the Mennonite congregation in Eugene, headed for Elkhart, Indiana, to attend the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries, and by 1981 we joined the Mennonite church and embarked on a long surprisingly fraught journey.

The writings of Norman Kraus were the starting point for all this. For better or worse, he played a foundational role in my life as a Mennonite. I personally would say absolutely for the “better.” I am deeply grateful for the role Norman played in my theological development, and in more recent years in my remaining in good standing as a college professor and pastor in the Mennonite world. Some who do not appreciate his theological journey (or mine) might say for the “worse.”

A kind of prodigy

Norman grew up in the Tidewater area of Virginia, near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, in a conservative, rural Mennonite community. He couldn’t wait to get away to go to college and beyond. He attended Eastern Mennonite College and immediately moved on to Goshen Biblical Seminary, impressing leaders enough there that he was hired at the age of 27 as a Bible and church history teacher at Goshen College.

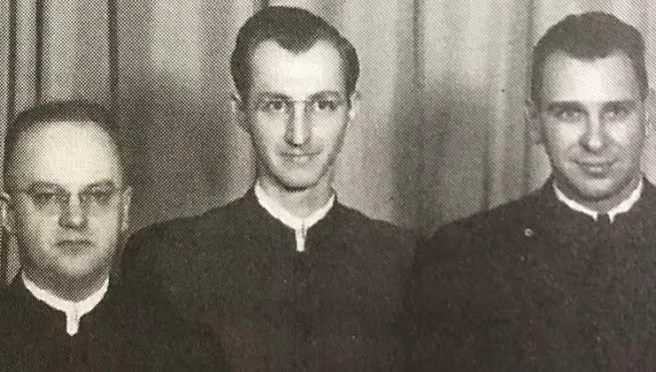

[This is Kraus in 1951 standing between his new Goshen colleagues J.C. Wenger and J. Lawrence Burkholder]

[This is Kraus in 1951 standing between his new Goshen colleagues J.C. Wenger and J. Lawrence Burkholder]

He remained at Goshen for the rest of his teaching career, though he took many opportunities to relocate for short term educational and ministry experiences. He studied at Princeton Theological Seminary and wrote a Th.M. thesis that was published by John Knox Press as Dispensationalism in America: It’s Rise and Development (1958). He started the project as an effort to understand the role of dispensationalism among Mennonites, but it was broadened to be what proved to be a pathbreaking effort at examining the role of this perspective on biblical prophecy among American Christians in general. This book played a major role in the thinking of historian Ernest Sandeen in his influential study, The Roots of Fundamentalism.

After a few years back at Goshen, Norman turned to completing his Ph.D. at Duke University, focusing more on theology. He spent the 1966-7 school year in India, teaching at Serampore Theological College. His next major book was The Community of the Spirit, that was published by Eerdmans in 1974, with a revised edition being published by Herald Press in 1993 and reprinted by Wipf and Stock in 2008.

Eerdmans also published a sequel, The Authentic Witness: Credibility and Authority in 1979 (reprinted by Wipf and Stock in 2010). Both of these books articulated an Anabaptist alternative to mainstream Protestant and evangelical understandings of salvation and Christian living. Norman argued forcefully for a unity between belief and action, with a strong emphasis on the role of what he called the Messianic community in the embodiment of faithful discipleship.

A turn toward a global theology

In 1980, Norman took a leave of absence from teaching at Goshen College and moved to Japan with his wife Ruth. They spent the next seven years working with the Japanese Mennonite churches. Norman taught at Eastern Hokkaido Bible School during most of this time, though also teaching for shorter periods in India and Australia.

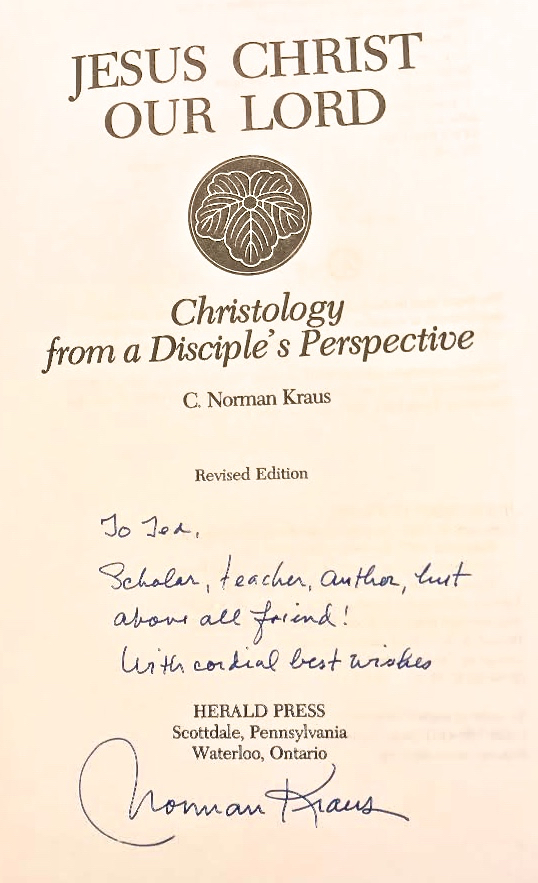

In response to a probing question from one of his Japanese friends about why Jesus had to be crucified, Norman immersed himself in developing a constructive christology that would attempt to answer that question in a way a non-Westerner might understand. The Krauses returned to North America in 1987 when Norman’s opus, Jesus Christ Our Lord: Christology from a Disciple’s Perspective was published by Herald Press. The book was popular enough that a revised edition came out only three years later (and it was reprinted by Wipf and Stock in 2004).

Norman followed his christology volume with a one-volume systematic theology, God Our Savior: Theology in a Christological Mode in 1991, also published by Herald Press (and reprinted by Wipf and Stock in 2006). These two books established Norman as perhaps the pre-eminent Mennonite writing doctrinal theology while teaching at a Mennonite school.

Jesus Christ Our Lord, in particular, created a sensation among North American Mennonites that is impossible to imagine in our post-theology context today. It was a serious, academic book of theology (though at the same time clearly written and accessible) that drew a wide audience. It particularly offended a conservative contingent of church leaders who were tone-deaf to Norman’s attempt to write theology that would make sense to those outside of North American evangelical Christianity. Norman’s proposals were not actually all that radical in the context of broader Christian theology—and they were certainly faithful to the Mennonite peace position, but he did not express them in traditional terms.

The hostility was intense. Norman told me many years later that he still felt hurt by the personal nature of many of the attacks and the failure of denominational leaders to offer him support. One booklet captures the spirit of the reaction—it was titled Christ or Kraus? During this time of publication and reaction, Norman retired from Goshen College and moved back to Harrisonburg, Virginia, with Ruth. He also suffered a major heart attack.

Norman regained his health and settled into an active retirement full of church involvement and continued scholarly writing. He published An Intrusive Gospel? Christian Mission in a Postmodern World (InterVarsity Press, 1998); To Continue the Dialogue: Biblical Interpretation and Homosexuality (Pandora Press, 2001) [Norman edited this book, a collection of essays taking various positions—it’s notable as the first publication that included Mennonite writers arguing for an inclusive stance]; Using Scripture in a Global Age: Framing Biblical Issues (Cascadia Publishing House, 2006); The Jesus Factor in Justice and Peacebuilding (Cascadia Publishing House, 2011); and On Being Human: Sexual Orientation and the Image of God (Cascade Books, 2011).

An important theological friend

I first met Norman in 1989. I had recently read his Jesus Christ Our Lord and reviewed it favorably for a Mennonite periodical. A friend of mine took me along to a planning conference in Chicago of the Mennonite Central Committee Peace Section. I was a new pastor, recently minted Ph.D. in Christian ethics, and an utter stranger to all these leaders of Mennonite peace witness.

I met several heroes—longtime leaders, Robert Kreider and Winfield Fretz, who I had learned about in my dissertation research on World War II conscientious objectors, and Vietnam War-era peace warrior Earl Martin, whose book on his experience of staying in Vietnam after the war ended I had just read. And, Norman Kraus.

Norman was interested in meeting me, too. He said he had appreciated my review; it was one of the best he’d seen. And he had wondered who this Grimsrud fellow was, someone he had never heard of. I can’t remember if our paths crossed over the next seven years or not, they probably did once or twice. Then, when Kathleen and I moved to Harrisonburg in 1996, the first Sunday we attended Park View Mennonite Church, there was Norman in our Sunday School class. So we renewed our acquaintance and we met Ruth. Sadly, shortly after that she was discovered to have cancer and died a few months later.

As I mentioned (and I told Norman about this as soon as I could), his writings played a major role in my entering the Mennonite world. And, I would say, he has remained throughout these past 40+ years one of my most important influences. I think he rates alongside Gordon Kaufman and John Howard Yoder as the most important of North American Mennonite theological thinkers. I studied with Yoder and became friends with Kaufman—and have written elsewhere about their importance. Though Norman did not have the wide, beyond the Mennonite world, influence of the other two, I think his self-conscious effort to write thoughtful but accessible theology made him perhaps the most authentically Anabaptist of the three.

I found it fascinating when I talked with Norman about Yoder. Norman of course knew Yoder personally quite well; they were students at Goshen Biblical Seminary together in the late 1940s and lived near each other in northern Indiana for many years. However, Norman said he didn’t know Yoder’s thought all that well, and that he hadn’t read many of Yoder’s writings. He rarely cited Yoder in his writings, and Yoder rarely cited Norman. I believe that their respective theological projects nonetheless overlap a great deal. To realize that they did not mutually influence each other indicates that each one was drawing on the same Anabaptist Mennonite tradition and applying the insights of that tradition to the contemporary world in impressively similar ways.

I used God Our Savior in my Introduction to Theology class for many years (and enjoyed having Norman regularly share with the class). The book was a bit of a stretch for most college undergrads, but I think it generally went over pretty well. Eventually, I wrote my own textbook (Theology as If Jesus Matters) that was greatly influenced by Norman’s approach, especially his profound strategy of addressing each theological theme through the lens of Jesus’s life and teaching.

I believe that Norman’s two big books (Jesus Christ Our Lord and God Our Savior) remain important resources for peace theology. I also believe that Norman did not receive the respect he deserved as a major constructive theologian. He is rarely referred to by younger Mennonite scholars. I hope, though, that some day his work will receive more attention. The central challenge the Anabaptist/Mennonite tradition faces today is to make its core convictions accessible and applicable in our post-denominational and post-rural Mennonite enclave world. Norman’s work is an important resource for that challenge.

An important ecclesial friend

For the first several years that Kathleen and I lived in Harrisonburg, we were part of the same church as Norman. I well remember sitting in on a fascinating Sunday School class that Norman taught for “skeptics” in the congregation. We left Park View when Kathleen began pastoring at Shalom Mennonite Congregation, but Norman and I still saw each other regularly. Interestingly, in the past few years we became part of the same congregation again when Norman and his second wife, Rhoda, began attending Shalom.

Norman played a crucial role in helping me navigate some of my stormy Mennonite waters. I came under fire from various sources due to many of my theological convictions. When I was being considered for tenure at EMU, some rather intense lobbying occurred in opposition to my being approved.

At one point, without my knowledge, EMU’s three top administrators called a meeting with one of my harshest adversaries and invited Norman to join them as an “expert” theological resource. Two of the administrators met with me to inform of this meeting afterwards. I was concerned (and angered a bit), but when they told me Norman was part of the meeting I breathed a sigh of relief. He did indeed offer a strong defense of my work, and after that, though the rest of the process included some intense conversations with the Board of Trustees, these administrators strongly supported my candidacy—which was approved. And from then until I retired in 2016, I felt solid support from EMU’s leaders.

At the same time as the tenure process was happening, I was also under fire within Virginia Mennonite Conference. Strong forces within the conference wanted to take away my pastoral ordination. This process included several meetings where I spoke with conference leaders. I was allowed to bring a companion with me to those meetings, and Norman graciously agreed to join me. I was gratified that he spoke in support of my ministry—and that as a consequence of those meetings shared many of my frustrations about the accusers. Eventually I was “exonerated,” thanks in part to Norman.

I was helped in both of these cases by Norman’s support. He was a highly respected person in the Mennonite community. In talking with him in the years since, I have gotten the impression that part of his willingness to invest himself in these ways came from his memory of his own struggles during the early years of his teaching career at Goshen College. He was considered theologically suspect by many in the Mennonite world and could empathize with the difficulties faced by theology professors who challenge received ideas.

An important dialogue partner

Over these past two decades, Norman and I conversed many times about theological themes. I genuinely felt we were kindred spirits. He continually inspired me with his agile mind, his undiminished curiosity, his remaining deeply engaged in the issues of the day, his insights and knowledge of Christian theology, and his positive spirit.

I did get him to talk at length one time about his own teaching career and some of the hurts he experienced due to insensitive administrators and unfair theological criticisms. As we neared the end of the conversation, he expressed a bit of embarrassment at being so candid. However, it was clear that the adversity had done little to embitter him or slow him down. He was driven by a passion to understand and to communicate. I think he looked back on his life as a reasonably successful effort at being true to that passion.

One of his most remarkable legacies, I think, is the collection of four books that he wrote over the final couple of decades of his life. He remained deeply engaged with the big questions and addressed them in profound ways into his seventies, eighties, and even nineties.

He wrote on evangelism in our postmodern, pluralistic age (An Intrusive Gospel?), arguing for a clear witness to Jesus as our definitive revelation of God combined with a deep respect for other religious traditions. He wrote on interpreting the Bible as a truthful source of guidance in our environment of relativism and the questioning of authority (Using Scripture in a Global Age). He wrote on how Jesus remains directly relevant for peacemaking, even as Mennonites and other Christian pacifists learn from more secular peacebuilding approaches (The Jesus Factor in Justice and Peacebuilding). And, he wrote on human sexuality and the debate about “homosexuality” in the churches (his essays in the book he edited, To Continue the Dialogue: Biblical Interpretation and Homosexuality and the book On Being Human: Sexuality and the Image of God).

Norman apparently left detailed instructions for his memorial service. It was well-planned and executed. And it was, fittingly, a kind of farewell lecture from a great mind and spirit. We heard moving remembrances from family and friends. And we heard some of Norman’s words—honest, insightful recent thoughts about death, dying, and resurrection. His iconoclastic impulses were represented, but even more his deep and abiding faith in the God of love he devoted his life to.

Hi Ted,

What a fitting tribute to Norman Kraus! You have increased my reading list by mentioning many of his writings.

Cliff Lind

Thank you for this beautiful tribute. It speaks very well of you both.

A fine eulogy, and lecture, of your own. Norman’s smiling face at the end makes an appropriate response. You strengthen his legacy.

Good summary and tribute, Ted. I remember meeting Norman Kraus in the early 70s when he invited me to participate in one of his classes at Goshen College. In retrospect, I’m quite sure I did not merit the invitation, but I read most of his books after that. I generally thought the older Brunks of his childhood and youth might stimulated much of his life-long theological mission. Levi

Truly enjoyed reading this!

Thanks for sharing this tribute, Ted! Norman spoke at a series of lectures at Trinity MC just over 3 years ago when he was traveling to Arizona. Very thoughtful and thought-provoking, and sharp as a tack at (then) age 91.

Kurt

Ted, It was so great to “hear your voice” as I read this. And fascinating for me to realize that I was introduced to Community of the Spirit at almost the same time. My copy still has the price written inside, 940 yen. I purchased it at a Tokyo bookstore on the recommendation of a Mennonite missionary friend in Tokyo before I came to Eugene and met you all in 1977. What an impact Norman Kraus had around the world.

Thanks, Norm—it’s really good to hear from you.

I guess that we had both read Kraus was one of the reasons we so quickly realized that we were kindred spirits! Hard to believe that was over 40 years ago…