Ted Grimsrud—November 4, 2025

The several years following World War II emphatically stamped the United States as an imperial power, not one that would seek to further the ideals of Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech of 1941 (such as self-determination and freedom from war everywhere on earth). As articulated in Harry Truman’s 1947 “Truman Doctrine” speech, instead the US would commit itself to be ready to intervene militarily everywhere on earth in order to defeat its enemies. Though the practices of the American Empire in the quarter century after World War II contradicted the ideals of the Four Freedoms, most Americans embraced an uncritical nationalism that prevented them from a clear-eyed view of their country’s actual way of being in the world.

From the colonial era through World War II, the North American colonies and the US pursued a domination agenda. From the start, the colonies utilized the superior firepower of European weapons to displace indigenous peoples and created an economic system that required coerced unpaid enslaved labor. While the American Empire could have made choices that moved in more humane directions, the odds for such humane choices always remained small. At the end of World War II, American leaders faced perhaps the greatest (and last?) opportunity to choose for the more humane. The US could have actually committed to the ideals of the World War II purpose statements that reflected the long-stated democratic hopes in the American tradition.

A choice of paths

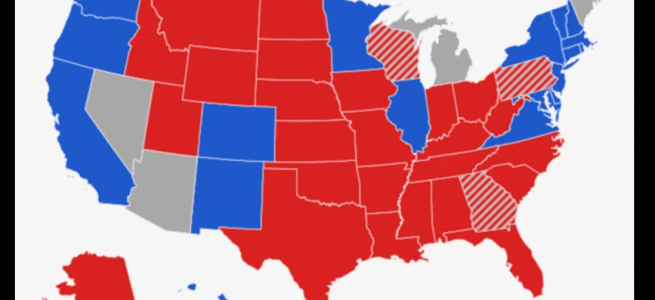

American leaders in late 1945 faced two basic options. One, the US could have pursued a multipolar world order. Such had been hoped for (but not achieved) with the League of Nations after World War I. Then, during World War II, many leaders expressed the hope that this time the great powers might do it right. They hoped for structures that would allow for many different power locations that would find ways to cooperate. These hopes led to the creation of the United Nations. This time, unlike with the League of Nations, the United States embraced its role as a world leader. In fact, this time the world leadership organization would be located in the US.

Or, in contrast, the world order could be based on the dominant power of a single nation and its close allies. World opinion at the end of the War did not allow for an open affirmation of such an approach. The two powers (Germany and Japan) whose open quest for world domination had been so devastating lost the War. No other power would dare advocate such an approach. However, the War ended with a single nation having achieved a dominant global stature that had never before existed. The US could seek dominance without openly claiming to.

The US found option two to be irresistible and embarked on a 50-year effort to establish and sustain a unipolar world order. However, the US “victory” in the Cold War did not result in American “full spectrum dominance,” an achieved unipolar world order. Rather, the years since the end of the Cold War have seen a steady diminishment of American power. Can the American Empire give up its quest for dominance and affirm the emerging multipolarity?