Ted Grimsrud—June 12, 2025

As a Christian, I read the Bible with two assumptions. (1) The Old Testament has its own integrity and tells its own story. It is not simply, or mainly, or even at all relevant only in relation to events far in the future of the story being told. (2) Jesus is the center of the Bible when read as a whole. He embraced the Old Testament as scripture and affirmed the messages of Torah and the prophets as revealing God’s will for the world.

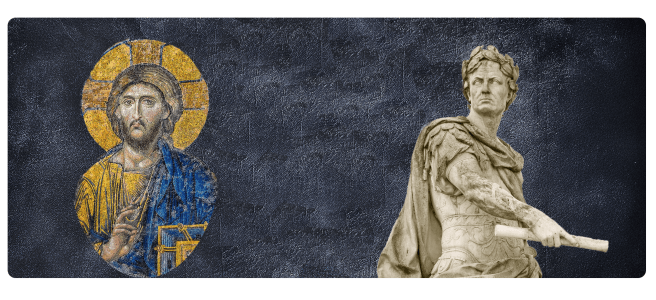

Jesus as the center of the Bible means his story clarifies and reinforces the basic message of the Old Testament. These two parts of the Big Story complement each other. Jesus embodies the political message of the Old Testament: critique of empire, rejection of territorial kingdom as the channel for God’s promise to bless all the families of the earth, and the embodiment of Torah as the alternative to the ways of the nations—including power as service, compassion and justice for the vulnerable and exploited, and resistance to the powers of domination. [This is the third in a series the Bible’s radical politics. Part one is “Ancient Israel among the great powers” and part two is “Ancient Israel as a failed state.”]

Politics and the gospels

One of the key terms in the gospels that signals their political agenda comes at the beginning: Matthew’s gospel tells “of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (1:1). “Messiah” equals “Christ.” Its literal meaning is “king,” a political leader.

We saw that the Old Testaments rejects the territorial kingdom as the center point of the peoplehood. It points to an alternative way to imagine peoplehood. The original promise from Genesis 12 that Abraham would bless all the families of the earth was not revoked when the kingdom failed. So, this is the question: If not as a territorial kingdom, then how will the promise be embodied? Jesus carries on this promise as “the son of Abraham.” Jesus will carry on the promise as a great leader for the peoplehood—yet he will also provide a different political path. That different path will be the story the gospels tell.

That Jesus was a challenge to the status quo may be seen with King Herod, the Roman Empire’s client-king in Jesus’s homeland. Rome faced resistance from the area’s Jewish people. Herod always felt his power to be insecure. A king arising to claim David’s throne posed a significant threat. When Herod learned of Jesus’s birth and his possible identity, he sought to eliminate the threat by killing all the newborn children in the area where Jesus was born (Mt 2:16). Jesus’s parents managed to escape to Egypt. The empire feared Jesus as a political leader who might to bring genuine justice to the families of the earth.

The name Jesus means “God saves” or “God liberates.” Just as the exodus followed by Torah empowered the community to further the promise of blessing, so Jesus’s story empowers for healing. Just as the exodus repudiated the ways of the Egyptian Empire and created an alternative, so Jesus’s ministry repudiated the ways of Rome and created an alternative.

The agenda of an upside-down king

Mark’s gospel begins with John the Baptist: “The voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord’” (Mk 1:3). John baptized Jesus, and God endorsed Jesus: “You are my son, the beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Mk 1:9-11). After this baptism commissions Jesus to begin his public ministry, he took a wilderness retreat. As “God’s son,” that is, as “Christ” or “Messiah,” Jesus has a kingly vocation. In the wilderness, Jesus encounters Satan, who tempts him: What kind of king will Jesus be? Will he claim dominating power or embrace a vulnerable power that involves suffering and even defeat? Satan offers authority to Jesus over “all the kingdoms of the world”—thus, the satanic nature of the power of territorial kingdoms. Jesus says no and sets off to present his alternative.

Jesus begins his public work and states his agenda: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the good news” (Mark 1:14-15). “Good news” (or “gospel”) is a term commonly used of the emperor’s deeds. “Good news of God” lets us know that Jesus brings an alternative message, not the priorities of the gods of the empire but the priorities of the God of the exodus.

“The kingdom of God is at hand” (Mk 1:15). By this, Jesus meant a community that would center on the love and justice articulated in Torah and be a contrast society in relation to the territorial kingdoms of the world. Jesus then offers a simple prophetic command: “Repent.” Turn from injustice and domination and false gods and turn toward the ways of peace, justice, and compassion.

Jesus gets to work

In Luke 4, Jesus introduces his work: good news to the poor, release to captives, recovery of sight for the blind, and freedom for the oppressed. In his “sermon on the mount” in Matthew, he applies the message of Torah. Like Moses, he guides his community to embody a counter-empire vision for life. He critiques ways Torah was interpreted in the tradition (“you have heard it said…, but I say to you…) in order to capture the essence of the original message, not to create something different. “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill” (Mt 5:17).

Jesus offered a succinct summary of Torah: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment. And the second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets” (Mt 22:37-40). This call to love serves as the first principle that animates and guides all the laws, guidelines, and organizing needed to sustain a political community. Jesus displaces the territorial kingdoms as objects of ultimate loyalty.

For Jesus to speak of a kingdom put him in direct conflict with the Roman Empire. He challenged the status quo with his love and compassion. Unlike most revolutionaries, he did not seek to replace the structures of domination through violence and more domination. His disciples did not understand Jesus’s alternatives and vied to be most powerful. He responded with his political philosophy: “You know that among the Gentiles those whom they recognize as their rulers lord it over them and are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you. Whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant.” (Mk 10:42-45).

Why did Jesus die?

A sense of impending conflict continually shadowed Jesus’s ministry. As he challenged the status quo and generated opposition he prepared his followers: “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23-24). To “take up their cross daily” underscores the political nature of Jesus’s work. The empire used “the cross” against people who undermined its power. Jesus’s work will inevitably be seen as a threat to the empire. Those who take it on must recognize the likely costs of doing so. Jesus faced conflicts from three directions: the Pharisees over how to understand and apply Torah, the Sadducees over the authority of the Temple, and the Roman Empire over Jesus’s messianic (kingly) identity.

(1) The Pharisees. After the destruction of the kingdom of Judah, many committed to work harder to shape life in Israel according to the law. The Pharisees became the main enforcers of these efforts. Jesus and the Pharisees had contrasting views of how the law should guide their opposition to the way of empire. Jesus emphasized that the deeper meaning of the law allows for flexibility in how details are practiced as long as we serve human well-being. The Pharisees pointed to strict consistency. Jesus and the Pharisees asked: How may the children of Israel live as a contrast society in relation to the Empire? Would the focus be on compassion and mercy or on purity and exclusiveness?

(2) The Sadducees (Temple leaders). King Herod had understood that to link the Temple with his authority would enhance his power. So, he led an ambitious building project that provided for centralized religion. The leaders of the Temple in Jesus’s day supported this arrangement. Jesus scorned Temple religion. When he directly pronounced people forgiven, he by-passed the Temple’s role in the process of dealing with sins—and drew the strong ire of the Temple leaders. The catalyst for his execution came when he entered Jerusalem and performed the symbolic act of driving money changers out of the Temple. When he said the Temple would soon fall, the Temple leaders arrested him and convicted him of blasphemy. They then turned him over to the Roman governor, Pilate, in hopes that he would be executed.

(3) Pilate. When Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God, he directly challenged the great empire of his day. He did not accept the empire’s claims that it brought the “gospel” (good news) of peace. And he rejected the claim that empire acts on behalf of God. Pilate ordered Jesus to be executed as a political revolutionary. That Jesus died such a death did make sense. He truly was seditious in relation to the state’s values. With Jesus’s execution, two contradictory notions of peace met head on. The Pax Romana (“peace of Rome”) relies on violence to maintain its hegemonic order. On the other hand, Jesus interrupts violence. He creates genuine peace by abolishing the notions of hierarchies and retributive violence altogether.

The meaning of Jesus’s resurrection

When God raised Jesus from the tomb against all expectations, God vindicated Jesus’s life as fully reflective of God’s will for humankind. The story of this life does not end with his death. By raising Jesus, God reversed any negative implications people might draw from Jesus’s life. The resurrection tells us that God absorbed the violence of the empire and nonviolently kept the promise alive. It underscores that the call to bless all the families of earth through embodied love remains in effect.

As well, in raising Jesus, God rebukes the Powers that put Jesus to death. Jesus’s critique of those Powers for usurping God reflected the will of the God of the universe. The structures and ideologies that buttress empire and religious institutions and cultural exclusivism combined to fight against Jesus’s expression of God’s kingdom. In doing so, they did not act as God’s agents despite what social elites always claim. They claim that their place at the top of society’s pyramid is God’s will and that their rule reflects that will. Jesus’s resurrection reveals such claims to be exactly wrong. The elites did not act on God’s behalf when they killed Jesus; rather they rebelled against God. The revelation of that rebellion as rebellion can help all with eyes to see to turn from trusting in those elites and their structures of power.

Revelation’s Jesus-based critique of empire

Revelation’s place as the final book of the Bible suggests that we may see it as a kind of coda to the entire Bible, a closing statement that presents the gist of the Bible’s message. The opening words of the book, “The Revelation of Jesus Christ,” assert that the book will be about the meaning and relevance of Jesus’s life and teaching for our world. The key point will be that Jesus’s witness displaces Rome (and all other human kingdoms) at the world’s center. John argues that the power that empire receives is due to deception. He seeks to debunk that power.

The big problem for John’s readers is the temptation to give loyalty to the Beast (or empire). The key vision in Revelation comes in chapter 5: the victory of the Lamb through his “blood” (faithful witness). From this comes universal worship of the Lamb; the Lamb usurps the emperor’s throne room.

What follows in Revelation will be the outworking of the Lamb’s already won victory. The plague visions in chapters 6–18 portray the on-going realities of human history. They underscore the need for present-day peaceable witness in face of the Dragon and the power of its deception. The Beast is very powerful (Rev 13) with power that comes from the Dragon but actually is given by the inhabitants of the earth (13:4)—based on deception and countered by illumination. We are free to refuse consent and thus undermine this power. Who can stand against the Beast? The Lamb and his followers (14:1-5). “The destroyers of the earth” (11:18) that must be destroyed are the rebellious Powers who inhabit the empires, territorial kingdoms, and nation-states of the world, not human beings themselves. These Powers fall (Rev 16–18) due to the faithful witness of the Lamb and his comrades. This witness debunks the deception of the Powers, taking away the consent that gives the empires their power.

Revelation’s final vision presents a city, New Jerusalem, that hosts healing and not oppression, characterized by a politics of love. This city embodies the Lamb’s witness as a counter-empire to Rome—no human hierarchy, no Temple, no domination. The Powers (ideologies, structures of oppression, hierarchies) are destroyed for the sake of human wellbeing.

Some concluding lessons

(1) The story of Jesus begins with an overtly political emphasis. He is identified in Matthew’s gospel as the “Messiah” or “Christ”—which means “king” (Matthew 1:1). King Herod learns of the Messiah’s birth and, feeling profoundly threatened, orders the murder of all the young children in the area. The story of Jesus is a story of two contrasting types of kings, two contrasting versions of the “kingdom of God.”

(2) One way to summarize the work Jesus did in his public ministry is found in Luke 4:18-19. He brought good news to the poor, proclaimed liberation for the captives, gave sight to the blind, and freed the oppressed. Jesus taught and embodied a politics of compassion, welcome, and care to the vulnerable and marginalized. He bypassed the existing political and religious institutions to bring healing and empowerment.

(3) When Jesus made the kingdom of God present, he inevitably found conflict with those invested in status quo social structures. The three categories of those hostile toward Jesus includes the Pharisees—who agreed with Jesus in challenging the empire’s agenda but disagreed about how to embody Torah, the Sadducees—who defended the centrality of the Temple, and Pilate, the Roman governor—who executed Jesus as a threat to the Empire.

(4) God brought the executed Jesus back from the dead. Jesus’s resurrection vindicated his way of life and the content of his teaching as direct expressions of God’s will for humanity. It also rebuked the institutions and ideologies that cooperated to kill him. Rather than serving as God’s agents as they claimed, they were proven to be God’s enemies.

(5) The book of Revelation provides a summary of the Bible’s core teaching. As a self-proclaimed “revelation of Jesus Christ” (1:1), this book presents two conflicting claims for loyalty—the “empire” of the Dragon vs. the “empire” of the Lamb. What matters most is loyalty to the Lamb that empowers “conquering” the Dragon through adherence to the Lamb’s way (Rev 12:11).

More posts on peace and the Bible—The Bible’s radical politics (part 1) (part 2)

In Matthew 5 the story of Jesus first Sermon, he preaches that the Kingdom of God is at hand, and this is the way to be part of God’s battle for mankind. Jesus said it’s not an eye for an eye (violence to repay hurt) but rather “Love your Enemy,” God’s Kingdom, the way of peace is the way of love, not merely rejecting violence, but by positively doing acts that love to our neighbors the way we love ourselves. Dave Jackson’s book “Is your God Good”, poses a whole set of interesting questions and approaches to understanding the violence credited to God in the Old Testament with the way of love taught by Jesus the Christ (God’s superhero royal heir) of the King David variety. Jesus says that love is God’s way to a redeemed mankind, hard as it is to see how love (shalom: peace) can really defeat all of the proud hate and evil in the battle around us.

I appreciate the good thoughts, Al. It’s good to hear from you again. I appreciate the reference to Dave Jackson’s book. I had not heard of it before. I’m glad he’s still writing. His Living Together in a World Falling Apart was very important book for me 50 (!) years ago. I had his daughter as a student.

Ted, this well-stated summary of the Bible’s core message and the centrality of Jesus as bringer of “seditious” (but non-violent) good news.

Now, Christians of almost all stripes see the Resurrection as critical, as you explain, mainly in its function as vindication. (As I understand what it appears to be via the greatly varied texts of the Gospels and Paul, it may serve as a message of victory over death as well, but vindication, inspiration, demonstration of connectedness is more the point… via appearances somewhere between apparitions and a corporeal [“bodily raised”] body.) Jesus’ death and resurrection I don’t see functioning as actually necessary for “reconciliation with God”… complicated theology there.

The main reason I raise this, from your core points, is to supplement more than take issue: I’ve long been convinced that even the “liberal” branches of the Church (variously “into” historical/literary criticism and symbolic interpretation) have failed to grasp what little can be reconstructed from late and minimal data as to the real nature of Christian origins. And, for purposes here, I’ll date that from the Resurrection.

As in other ways, I perceive that traditional Christian understanding of the Resurrection (and early “Church”) is overly wedded to the miraculous and to uncritical acceptance of jumbled “oral tradition” and legends of the Gospels, plus theological slant by the writers. Conversely, “progressive” churches and the scholars they look to, are not deeply enough probing nor “imaginative” (in a realistic sense) and not open enough to the “miraculous” (here used as “metanormal” rather than exceptions to natural laws… that is, less common, or “above” the “normal” occurrences like appearances of departed loved ones).

I believe a Resurrection understanding of this nature preserves the basic truth and power of the narratives, plus it allows us to really hear the earliest written testimony of encounter with the risen Jesus… Paul’s (esp. 1 Cor. 15). And with this, gain some reconciliation between the embellished accounts of the Gospels and the simpler but important statement by Paul that he was (perhaps) the “last” witness to the Resurrection, and in a way very similar to the Apostles and “above 500” before him.

I held the basic ideas of this understanding for a good number of years, but it was brought into greater clarity and I believe, strongly supported by the deepest, most thorough examination of the topic biblically, with adjunct accounts of experiences and evidences that relate. It is “The Resurrection of Jesus: History, Apologetics, Polemics” (or very similar title), by Dale Allison, a top Jesus and NT scholar who is Christian. Highly recommended, though not for the uninitiated or those with low motivation to stick with his level of detail and academic style.

Thanks, Howard. I like what you say and appreciate the reference to Allison’s book (I’ve read some of his other stuff but not this).