Ted Grimsrud—May 20, 2019

I can imagine several ways that the question I ask in the title of this post could go, so I want to start by explaining what I mean. By pacifism, I have in mind the principled unwillingness to support or participate in warfare or other forms of lethal violence (though I will say a bit more below that will define pacifism in more detail). For the purposes of what I write here, I assume the validity of pacifism. My question has to do with whether there is a type of pacifism that is uniquely Christian—that is, in effect, only available to Christians.

To make this more personal, I can rephrase the question: (1) Am I a pacifist because I am a Christian? Or, (2) Am I a Christian because I am a pacifist? Which comes first? Which is more essential? Now, of course, most Christians are not pacifists. And surely many pacifists are not Christians. As I have thought about this lately, I have come to conclude that though my self-awareness of having an explicitly pacifist commitment came at a time when I would have believed #1 (that I was a pacifist because I was a Christian), I now think that #2 is true for me (that is, to the extent I would see myself as a Christian it is because I am a pacifist and I know of a kind of Christianity that affirms pacifism). I should also say before I go further that I recognize that so much of this kind of discussion depends on how we define our terms. I will try to do that with care as I move along—but I request of the reader some tolerance with the limits of our language. I offer these reflections more as a kind of thought experiment than pretending to present anything definitive.

A uniquely Christian pacifism?

I grew up mostly outside the church, and in a general and vague way I found war and other forms of violence pretty unattractive, mostly on humanistic grounds. My father had fought in World War II, but afterwards refused to have a gun in the house, saying he had seen enough guns to last a lifetime. My mother had also served in the military during the War, but certainly never valorized doing so.

When I was 17, I was encouraged by several important people in my life seriously to consider seeking an appointment to one of the military academies for college. I don’t remember the conversations very clearly, but in my memory is a sense of feeling that such a journey was not even remotely attractive. This was partly because of watching the Vietnam War on television and seeing it as deeply problematic. But it was also simply not being able envision myself as a soldier trained to kill other human beings.

Interestingly, the same summer that I had the most intense conversations about my possible future in the military I also had a conversion experience and embraced Christianity. Tellingly the Christianity to which I was initially exposed had no qualms about affirming the soldier’s path. For several years, it never occurred to me that Christian faith might lead one to reject fighting in war. My reluctance to go to war was much more intuitive.

About the time of my 22nd birthday, as I neared graduation from college with a journalism degree (I hoped to be a sportswriter), everything changed. The vagueness of my reluctance to be a warrior became a clear and specific conviction—I could never fight because I knew that it would be wrong to do so. This became a certainty (as it has remained)—and seemed at the time to be directly tied to my Christian faith. As I look back, though, I realize that at that moment I knew nothing about any Christian pacifist traditions or any explicit Christian peace theology. I’d had no conversations with other Christians about pacifism. I’d say that it actually was more a personal awareness about the wrongness of war than a specifically Christian belief.

My vagueness soon changed, though. My faith-seeking-understanding concerning my pacifism led me to discover Mennonites. We had a few Mennonites in our college town (Eugene, Oregon), and I tracked down numerous books and articles. A few years later, my wife Kathleen and I attended a Mennonite graduate school and I got an MA in peace studies. Then followed formally joining the Mennonite church, becoming a Mennonite pastor, and getting a PhD in Christian Ethics with a dissertation on conscientious objection to World War II.

During these years, I came to believe that my pacifism followed from my Christian faith and was shaped by that faith in ways that made it different from any other kind of pacifism. Jesus Christ taught and practiced the love of enemies and he is God’s Son. His path is costly and, ultimately, not based on beliefs about effectiveness. We count only on God’s vindication—which may take the shape of failure (even death) followed by the miracle of resurrection. At the center was the inextricable link between Jesus’s identity as God Incarnate and the truthfulness of his call to follow his pacifist path. His call made no sense and had no power apart from his identity.

I’m not sure, though, that that logic ever actually animated my pacifism at its core. I suspect that for me it was more a matter of believing that I should have an explicitly Christian rationale for any strongly held believe—and then trying to find such a rationale. Certainly, I now realize, my entry into my pacifist convictions was not based on theological reasoning. At the same time, it is not that I now believe that the Bible and Christian theology don’t support pacifism (nor do I no longer believe that Jesus is God’s Son). I do think the best reading of the Bible and the best understandings of Christianity’s core convictions point toward pacifism (I still affirm the two books I wrote making that point—God’s Healing Strategy and Theology as if Jesus Matters)—and I do think Jesus is God’s Son. But I now tend to see that my pacifist convictions are based on something deeper (and perhaps more fundamentally human, even universal) than the scriptures and theology of one particular human-generated religion.

Questions about Christian pacifism

As I said above, my initial experience as a Christian convert was in a church environment that was quite pro war—even militarist—in sensibility. So I have known all along that most Christians are not pacifists. That means most fundamentalist Christians and most liberal Christians. Most deeply involved and pious Christians and most marginally involved and profane Christians. Most high church Christians and most low church Christians. Most highly educated Christians and most lightly educated Christians. Most North American Christians and most Global South Christians. Even, most Quakers and, I daresay, most Mennonites. Most Christians (in many contexts, all Christians) reject pacifism.

In other words, it is simply a descriptive reality that very few Christians see an inextricable link between Christianity and pacifism. And that is not because too many Christians are, sadly, misinformed about Christianity or unserious about their faith. Certainly, many Christians are misinformed and unserious. However, most of the most informed and most serious Christians also are not pacifist. Maybe I could say that after more than forty years, that non-pacifist consensus is wearing me down. It does not make me doubt the truthfulness of pacifism when I realize that Christianity is, as a matter of fact, a non-pacifist religion. It does makes me doubt the truthfulness of Christianity (which does not mean doubting the truthfulness of the Bible or the truthfulness of Jesus).

I noticed a number of years ago when I read the 1995 Mennonite Confession of Faith carefully that this confession, though it does eventually affirm pacifism, presents its core doctrinal teachings (in the first eight articles) in a way that does not take pacifism into account. It seems as if the writers of the Confession wanted to make it seem as compatible as possible with the major Protestant traditions (none of which, of course, affirm pacifism at all). So, even for Mennonites, the core convictions of Christian faith do not require a pacifist sensibility (in contrast, see my attempt to write about the core convictions that does make pacifism central—Theology as If Jesus Matters: An Introduction to Christianity’s Core Convictions).

I think it is also a matter of historical fact that the vast majority of Christians since the rise of the Western nation-states have simply given their respective governments a blank check and willingly supported preparing for and fighting in whatever wars the state might engage in. I researched conscientious objection in the United States during World War II and discovered that the government recognized about 12,000 COs and excused them from military service—and drafted more than 12,000,000 soldiers into the military. Noting that most of those in either group would identify as Christians, we could make a ballpark estimate that one out of 1,000 American Christians was pacifist (0.1%)—that is, hardly any. It seems clear that there is nothing inherent in the actual embodiment of Christian faith that leads to pacifism.

I assume that there is a connection between a doctrinal system that does not make pacifism a part of its core theology and a willingness automatically for church members to go to war. We can construct a rationale for pacifism based on Christian theology, but I don’t truly think that we can call pacifism “Christian.” A kind of pacifism that presents itself as being uniquely Christian does not seem consistent with the understanding of Christianity that characterizes almost all Christians, at least since the 4th century and that affirms war.

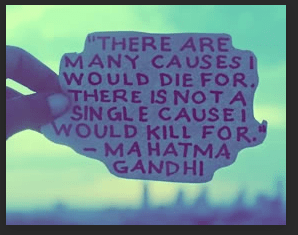

I also have recognized for a long time that not all pacifists are Christians. And these are not only “pacifists” who merely see nonviolent tactics as the most effective way to achieve political goals. There are also non-Christian pacifists who are pacifists because they believe in and practice love for their enemies, even at great cost to themselves. Whatever it is that empowers a person to give up their lives out of love for others is present with at least some non-Christians.

So, I have not observed a positive correlation between Christian faith and the practice of self-giving love and refusal to use violence. Certainly many people who seek to follow Jesus and affirm orthodox Christian beliefs do practice self-giving love in impressive ways. But others practice that kind of love in equally impressive ways and do not believe themselves to be Christians. Praise God for both kinds of people!

Pacifism for everyone?

A key point for me is to expand the definition of “pacifism” beyond simply a rejection of war. I do think that rejection is an important aspect of the meaning of pacifism—and separates “pacifism” from merely “loving peace” or affirming “nonviolence”. However, I believe that pacifism signifies more than saying no to war and violence. It signifies a positive affirmation of the centrality of love for human ethics—not simply a negative stance regarding violence.

And I believe that the centrality of love is a core part of who we all are as human beings. We are all born needing connection with others and love is what empowers that connection. We are fragile creatures who easily are damaged and in that damage turn away from love—and the damage spreads to cultures and we grow up socialized by damaged cultures. But love is what drives us and living in love is how we best fulfill our human nature.

So, I don’t believe that the story of Jesus and his love distinguishes biblical faith from the rest of humanity. All cultures over all history have been healthiest when love is central (I state this more as a philosophical affirmation than as the result of careful scientific study—though the latter could possibly disprove the former should such a study be done). Biblical faith can confirm the broader human experience and provide a metaphysical framework for understanding it (e.g., the idea that we are created in and for love by a loving creator based on materials such as the creation story, some of the psalms, and teachings found in the gospels). However, we do not need the Bible to recognize the foundational reality of love.

Let me suggest that the dynamic is not that we start with the normal, innately human way of seeing life as inevitably violent and it taking “special revelation” to see something different. Rather, I believe that the normal, human way of seeing tends more toward pacifism and that the affirmation of violence is due to cultural deception, the consequence of what the Bible calls “idolatry” where people trust in nations and ideologies instead of the true God of love. “Special revelation” is not then special information from the outside that is not discernible to normal people but rather a cutting through of the idolatry to help any of us see how things truly are.

I will close with a suggestion that we can think of “Christian” pacifism in one of two ways. One way would be to say that there is a pacifism that is uniquely Christian, that depends upon God’s special revelation in Jesus and requires an affirmation, we could say, of a faith about Jesus—confessing his identity as God Incarnate as the basis for self-sacrificial love, even of enemies, and a willingness to die for one’s convictions. Such a pacifism stands or falls on this confession.

The second way would be to say that to live with love as our central moral imperative so that violence is always forbidden is simply the consequence when we recognize and affirm the universal human reality of love as our core reason for being. Christian faith is only one way to recognize and affirm that reality. Christian faith is true and worth embracing only insofar as it does empower such a recognition and affirmation. The distinctive elements of Christianity—its creeds and other doctrines, its rituals and sacraments—have their validity in providing such empowerment. Insofar as those distinctive elements become “autonomous” (or, ends in themselves) and comfortably coexist with war and violence, they lose their authenticity and contradict Jesus’s (and Torah’s) placing love as the incontrovertible center of faith.

In light of these points, I would say that Christian pacifists should not seek to present their convictions as unique or better than other forms of pacifism that place love at the center. For a pacifist to affirm that Christianity is true because it puts love at the center will then celebrate of other forms of pacifism that also put love at the center. Pacifism them becomes a basis for welcoming people of other faiths (or none), not another rationale for pride and exclusion.

The pacifism of early Christians was based on a spaciously Spiritual perspective wherein our realization of our fundamental unconditional being was dawning.

The resurrected, in the celebration of their shared unconditional being, co=create a pacifistic shared reality (I go to prepare a place) – not a dog eat dog world such as we participate in here. Their “kingdom” does not belong here” and we too may out grow this world. This “room” is one of violence and excess. We are here because, for the moment at least, We very much belong here. We revel in the gore and the “glory” of war and such (predation) and thus seek to violently impose our will and our way upon Others. There is a way out of this mess and when We truly seek it We will be on our Way to finding it. For the moment We are where we belong and pacifism is dysfunctional in these surroundings.

The more I ponder pacifism the more I have come to appreciate Buddhist pacifism. It generally avoids the love word and the God word and thus avoids adding to the attachments of the erotic and the political (power) whi

Wilson, I’m with you about early Christianity. The decisive point is the expectation of a future in the realms of heaven which makes Christians aliens in this world. As aliens they are shy to intrude too deeply into the affairs of the this-worlders, shy to take sides and take part in fights – wilful to help, where their help is wished, but just as wilful to retreat where they are seen as obtrusive – read for that the “Letter to Diognetus”.

I also see a similarity to Buddhism – Buddhism is somewhat older and probably has had an influence on the development of out-of-world religions western of India.