Ted Grimsrud—November 21, 2025

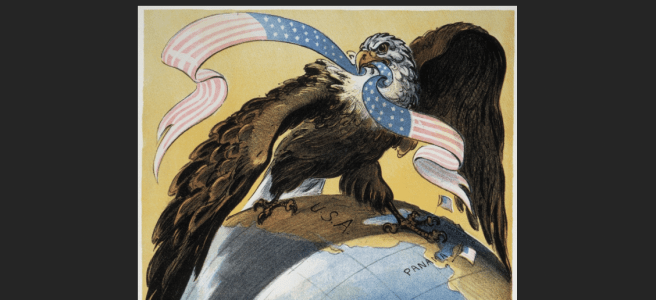

I have found Christian pacifism, properly understood, to be a most helpful framework as I try to understand the world I live in. In this series of 24 blogposts, I explain how I came to affirm pacifism and what it means for me. I have also showed how my pacifism shapes the questions I raise and criticisms I offer in relation to the American Empire. In this final post, I offer reflections on moving forward to live in the Empire in light of pacifist convictions.

Rethinking power

Christian pacifism posits two central affirmations— (1) We are called to resist and to seek to overcome evils in the world (“evil” most simply understood as that that harms life) and (2) We must work against evils in ways that do not add to the evil. The practice of pacifism helps us hold these two affirmations together. Committed to overcome evils, we engage the American Empire, the source of so many evils in our world. Committed not to add to the evil, we seek to find consistently nonviolent means as we strategize and act. One of the main ways human beings have tended to add to evil is to resist the wrong through the use of violence and coercion.

The American Empire cannot realistically be transformed in any immediate way. To try too hard to transform the Empire may lead us to take moral shortcuts that change us in ways that result to our actually adding to the evils that the Empire is doing. Violent resistance uses evil means to seek what might be good ends and may transform the effort into something that adds to the evil. On the other hand, many people try to reform the Empire through efforts that all too often actually result in compromise with the Empire on key issues and little genuinely changes.

We should recognize, then, the problematic character of conventional, top-down politics. Let’s use the term “Constantinianism” for politics that both tries to control history by making it turn out right and uses top-down power that is coercive and dominating. The embrace of such methods ensures that our efforts will add to evil, not overcome it. Pacifism understands power in a different way. It recognizes that we are not in control and that the only way to overcome evil is always to act consistently with love. One of the great insights of Gandhi and King was to recognize that ends and means must go together. We only achieve genuine healing when we act in healing ways. Violent and coercive means cannot achieve healing ends.

Continue reading “Conclusion: A Christian pacifist in the American Empire [part 2]”