Ted Grimsrud—October 17, 2025

The Bible has a reputation of being pretty pro-violence. Some Christians want the Bible to approve of violence—that helps them justify the violence they currently support. I decided back when I first embraced pacifism that I wanted to try to read the Bible as pro-peace as much as I could. I still do. An early test for me came with trying to understand the book of Revelation. Is it truly about visions of future God-approved warfare and violent judgment?

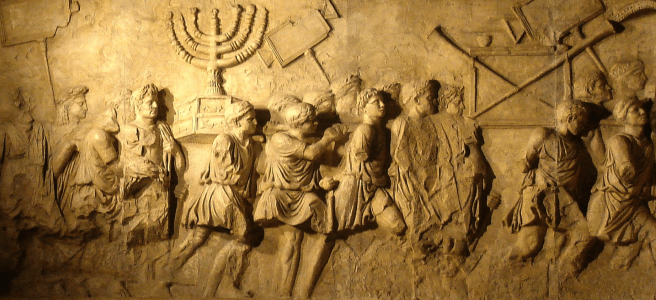

I had heard because God wants wars in Revelation, God may also want wars in our time. I decided to study Revelation to see what it actually says. I soon discerned Revelation may be read as a book of peace. I also realized that Revelation is not about predicting the future; it is about applying Jesus’s message of peace and healing in our present. A key concern in Revelation has to do with following Jesus while living in the idolatrous Roman Empire. Thus, Revelation becomes for us an essential text for reflection of the relation between Christian faith and empire.

Revelation as part of Jesus’s peace agenda

For Jesus, to resist the Empire means: Love our neighbors, say no to idolatry, give our loyalty to the God of mercy, and recognize the empire as the enemy of God, not God’s servant. Early Christians faced constant temptation to conform to Rome. It could be costly to resist. Many also found the imperial claims to be seductive. This struggle with conformity to the empire had a tragic ending for Christianity; we will see in our next post that it became an empire religion. In the early years, though, the struggle led to a sharp critique of the Empire—see Revelation.

Revelation does not collect predictions about “End Times” but describes the dynamics of imperial seduction. It describes the deep conflict between the ways of empire and the ways of the gospel. This “war of the Lamb” can only be successfully waged in one way. Wage this war with what the New Testament letter to the Ephesians described as the “whole armor of God”: The belt of truth, the breastplate of justice, the gospel of peace, the shield of faith, the helmet of salvation, and sword of the Spirit (which is the word of God) (Eph 6:13-17).