Ted Grimsrud—October 28, 2025

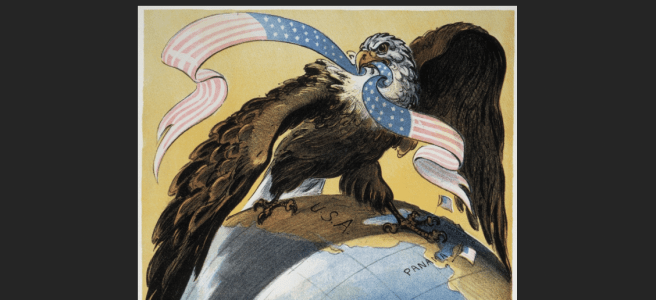

In the posts that remain in this series, I want briefly to flesh out what we see when we describe without blinders the American Empire as it has emerged and functioned over the past 500 years. I consider this story with a critical perspective shaped by the biblical politics I have summarized above. I am especially concerned with how this Empire has embodied oppressive and violent sensibilities typically characteristic of the great empires of the world. A clear-eyed look at the American Empire may well lead one to recognize that it is not worthy of the kind of blank check loyalty it asks for.

The reasons that Europeans first moved to settle in North America varied greatly. Their impact, though, was to extend the newly emerging European empires with powerfully devasting effects on the inhabitants of the “new world.” Some Europeans stayed only temporarily, mainly having interest in profiting from their time away from home before they would return from the adventures and resettle in Europe. Many, though, intended the trip from the start to be one-way. Those who meant to stay in North America may be called “settler colonists.” Since they intended to stay, they needed to displace those already living on the land. Settler colonialism depended on violence. It reflected the basic assumptions of empire: The people not part of the core colonial community will be seen as “Others” who may be exploited, displaced, even eradicated.

Settler colonialism and Manifest Destiny

Imperialistic ideology had been central in the settling of North America and remained central to the identity of the newly established United States. The new nation continually expanded West, dominating and displacing the indigenous nations without pause. The land taken from the natives came to be worked by massive numbers of forcibly imported enslaved Africans.

The term “Manifest Destiny” was not coined until 1845. However, its basic meaning that God willed the expansion of the US to the Pacific Ocean characterizes the intentions of the new settlers from early on. Throughout the colonial era and beyond, Americans simply assumed that God had called their nation into existence, a sense of divine calling that lent an air of inevitability to the expansionist efforts. God supported displacing the “heathen” indigenous populations and exploiting the “heathen” enslaved Africans. Once the drive to expand the US Empire across the continent took hold, it would not stop when the “frontier ended” in North America by the end of the 19th century. At that point, the empire was only getting started.

Displacing the original inhabitants

In 1491, the year before Columbus landed in the Caribbean, the indigenous population in the Western Hemisphere may have been up to 100 million. This estimate is speculative, but the devastating effects of the European invasion cannot be denied. The population dropped radically as the Europeans crushed existing cultures. They may not have intended to wipe out the native peoples as quickly and decisively as happened. However, they did intend to take over the land.

Settlers and the military drove most of the natives west to the territories in agonizing “trails of tears” with massive casualties along the way. The relentless expansion of the US westward led to continuous violence as the military went ahead of the settlers to drive out the natives. The soldiers dispatched those who resisted with merciless brutality. A remnant survived, mostly in carefully isolated reservations usually on land undesired by the settlers.

American imperialism drove the nation long before the 20th century growth of the Empire throughout the world. Empires disregard the rights and integrity of native peoples who stand in the way. The record of violence, disregard for agreements, and other forms of dehumanization in relation to the original North American inhabitants clarifies as nothing else the imperialistic character of the United States from its very beginning and throughout its history.

Building an economic powerhouse on the backs of forced labor

The enslavement of captured Africans by Europeans dates back at least to the mid-15th century. Spaniards brought the first enslaved Africans to the New World by 1501. The British brought the first enslaved Africans to Virginia in 1619. Unlike with indentured servants, the colonists forced Africans to remain permanently enslaved; likewise with children born into slavery. In the years that followed, slavery played a key role in the economic development of the colonies. However, the role seemed to diminish shortly after independence. That trend reversed, though, when new inventions made growing and exporting cotton extremely profitable. The American South transformed from an area dominated by worn-out tobacco plantations to a continental cotton empire. This transformation fueled the growth of the US into an economic powerhouse. The ability of the cotton industry to become so profitable depended on the extraordinarily violent use of enslaved people’s uncompensated labor.

The issue of the legality of slavery played a central role in the growth of regional conflicts in the US that culminated in the Civil War. Though slavery formally ended in the US at the conclusion of the Civil War, the generative dynamics of white supremacy and race-based enslavement did not end. On-going violence against nonwhite indigenous North Americans, the expansion of the US Empire globally mainly through the exploitation of people of color, and the emergence of the Jim Crow South underscore the persistence of white supremacy.

The conclusion of the American Civil War allowed the nation to focus its energies on completing the conquest of the rest of the “continental” United States. These imperialistic wars were fought against native sovereign nations trying to retain their independence. The Civil War accelerated US militarization. Leaders now saw war as effective and necessary to further their intentions. When the indigenous peoples would not simply submit to the US government’s dictates, overwhelming force became the main technique to assure the desired outcome.

The American Empire grows beyond North America

The first US war outside of North America began in 1899 in the Philippines following after the 1898 Spanish-American War. The war with Spain emerged from US aid to a revolt in the Spanish Cuban colony. After helping the insurgents eject Spain, the US turned against the Cubans and established Cuba as a subservient “protectorate.” This exploitative relationship culminated in the Cuban revolution that overthrew the US puppet leadership in 1959.

The Americans also expropriated Spain’s island colony of Puerto Rico and sought to do the same with the Philippines. The American navy quickly dispatched the Spanish colonialists who had fought against Filipino insurgents. Like with Cuba, the US quickly turned on the insurgents in order to assert American control and prevent genuine independence for the colony. This time, though, the insurgent resistance proved to be difficult to subdue. A full-scale guerilla war ensued that led to several thousand American and over 200,000 Filipino deaths. American firepower prevailed, and the Philippines became an American possession.

The “American Century” begins

The takeover of the Spanish colonial possessions set the US up to expand its economic interests and project its military power to the Far East. President Theodore Roosevelt helped facilitate Japan’s emergence as a major power. Japan’s growing assertiveness in time led to a rivalry with the US leading to World War II. After Roosevelt left the presidency in 1909, though, the US slowed down on colonial expansion. Many American elites continued to envision a major role in the global order for the US. This proved to be a gradual process.

The next major step in the development of the American empire came with the nation’s shrewd strategy of reluctant participation in Europe’s “Great War.” Woodrow Wilson, American president from 1913–1921, supported the British after war erupted in Europe in 1914. A careful propaganda campaign persuaded reluctant Americans to join Britain and go to war against Germany in 1917. The Americans helped turn the tide in what largely had been a stalemate, but the US did not suffer the destruction of its infrastructure and economy that befell the European nations. This strengthened the US global economic standing but Wilson’s hope to exert more influence in postwar global politics ended up constrained by strong political forces at home that feared more involvement in the conflicts of “foreigners.”

During the 1920s, a series of Republican presidents returned to “normalcy” following the stresses of Wilson’s war. The US did little to build up its military power and extend its imperial reach. At the same time, the seeds for future conflicts—especially in Eastern Asia—continued to be sown. However, American leaders essentially put the expansion of the American Empire on hold. They awaited another global trauma that would transform the place of the US in the world—and definitively put an end to American isolationism.

Franklin Roosevelt campaigned in 1932 with a promise to confront the Great Depression, not to expand the US Empire. Only after the war clouds over Europe and the Far East grew in the second half of the 1930s could he take a more outward focus. In 1937, the US military stood as only the world’s 16th largest, just behind Romania. In face of the rising tensions with Japan and Germany, American internationalists argued for American intervention. Roosevelt recognized that the American people remained resistant to the nation becoming “entangled” in other’s wars while he gradually pushed for intervention, first by increasing the size of the American military. He strengthened ties with the Nationalists in China and with Great Britain in Europe.

In the late 1930s, Americans watched frightening newsreels, and their foreboding grew. Still, the interventionists stopped short of calling for war. Yet, all of the rhetoric in favor of increased intervention assumed that the only way to deal effectively with the crises would be direct military action. The conflicts in Europe accelerated in September 1939 when the Germans invaded Poland, quickly defeated France in June 1940, and turned on the Soviets a year later. A full military engagement became inevitable. Likewise, Japan’s war against China showed that an eastern war had also become inevitable for the US. It still took time for the American leaders to rally broad support across the society. For the last time in American history, a desire to go to war by the power elite would be constrained by the need for a formal declaration of war by Congress.

Roosevelt worked gradually to win over public opinion in favor of a war declaration. In the meantime, he continued surreptitiously to expand American efforts to support the Allies. The US provided Great Britain and China extensive military aid and other forms of support. The US stayed “neutral” in these conflicts in only the most formal sense. The needed catalyst for US entry into full-on war came with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

Ready for the imperial moment

In the late 1930s, various American leaders began to sketch a vision of a world order following the coming war. They anticipated an inevitable, if costly, victory in this war. They resolved to be ready to take advantage of the situation and to ensure American leadership in the new global system that would follow. The US emerged from the War as the undisputed leader of the world. American leaders embraced that new status, and the era of American global hegemony began. This full-on imperial America was not the result of a philosophical change of direction. It was not that America had heretofore been a modest, internally focused nation only reluctantly thrust into the role of global leadership. An ambition for empire characterized the major currents of America’s political elite from the earliest colonial days.

When the catalyst of total war that brought all of the other world’s major powers to their knees arrived, American elites were ready to have their ambitions realized. Though the country had always seen itself as on a mission from God, the shape of that mission was never determined by the actual content of biblical politics. Its stated ideals sometimes echoed biblical values such as care for the vulnerable, social justice, and restraints on warist dynamics. The operative values, though, always echoed instead the values of the great kingdoms that stood against God.

[This is the 17th of a long series of blog posts, “A Christian pacifist in the American Empire” (this link takes you to the series homepage). The 16th post in the series, “The tragic American Empire story in light of the gospel,” may be found by clicking on this link. The 18th post, “The war that changed everything” may be found by clicking on this link.]

Good summary history… and important!

As an educator, I’ve been thinking about the various components needed to make, as you say, our “stated” values into our “operational” ones. Some of those components I’m convinced exist in the kind of massive (but DOABLE) reforms of our representational, electoral and balance of powers systems I’ve spoken just a little about in recent comments.

But I’m wondering if you’d expand these elements further and brainstorm with me, and hopefully others, on the specifically educational and “spiritual community” aspects that we might implement (or improve). That would include but not end with education and community spiritual PRACTICES via local churches, private K-12 schools, higher ed, and homeschooling.

My Evangelical/Charismatic relatives and friends would emphasize “revival”, with some claiming it’s happening NOW on college campuses (not just via the late Charlie Kirk and TPUSA chapters). They aren’t entirely off base.

But that’s a complex subject and the typical understanding and management of such a dynamic has so far only produced very mixed results… even the best parts being short-lived for the most part.

Your thoughts?