Ted Grimsrud—October 10, 2025

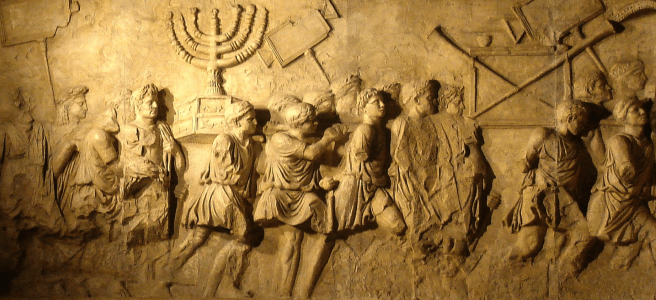

Peace theology centers on Jesus’s life and teaching. Jesus’s life and teaching, though, make the most sense in relation to the bigger story of the Bible. In two posts, I will emphasize a few elements of the story. First, in my previous post, we note the Bible’s strong antipathy toward the big empires. Those empires powerfully challenged the Bible’s faith community—due both to the empires’ violence directed at the community and to the empires’ demands (often met) for loyalty and even idolatrous trust. The Bible offers a counter-empire vision for human life in the teaching of Torah and Jesus. These teachings explicitly offer alternatives to empire ideologies.

Second, Torah politics differ from state politics. Territorial kingdoms and nation states imitate the empires. They use coercion, exploit the vulnerable, protect boundaries, and demand absolute loyalty. The Bible’s faith community, called to bless all the earth’s families, sought to carry out that vocation as a territorial kingdom. The story shows the eventual incompatibility between the vocation to bless and identifying too closely with a territorial kingdom.

Abraham and Sarah and a new intervention from God

Genesis 12 tells of God calling Abraham and his spouse Sarah to parent this community. God gave them a child even though Sarah thought herself too old to bear children. The story that follows in the rest of the Bible presents the community in both success and failure. It offers guidance for the faithful practice of a politics of blessing. The continuation of the promise will be risky and tenuous. The human actors always risk derailing the process by their injustice, violence, and turning toward other gods. The channels for the blessing will always be imperfect human beings. The process will often be surprising. Key actors consistently will not be the people we would expect to be heroes. God’s hand in the dynamics is often difficult to discern, but somehow the promise and the blessing remain alive.

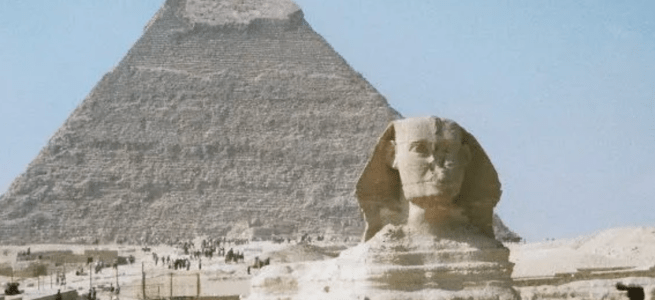

At the end of Genesis, the family of the promise moves to Egypt in order to survive a terrible famine. Then, in the book of Exodus, we learn the family does survive and multiplies, but in a condition of enslavement in the Egyptian Empire. These suffering, enslaved people cry out in their pain. God remembers the promises to Abraham and resolves to intervene. God will guide them into a recovery of faith and a new resolve to embody the promise to be a blessing.

Continue reading “Breaking the hold of territorial kingdoms”