Ted Grimsrud—October 24, 2025

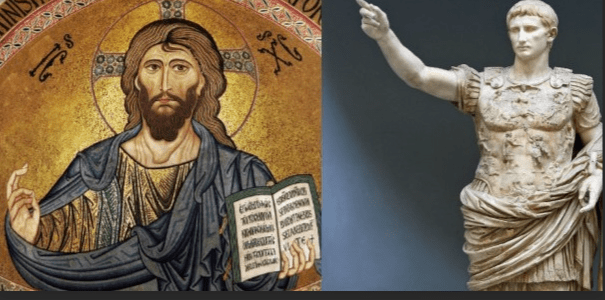

I recognize my upbringing as a proud citizen in the world’s most powerful empire to be part of my identity. As I described previously, I experienced an eventful meeting between two world-defining stories—the American Empire met Jesus’s gospel of peace. American Christians tend to see faith and nation as fully compatible, even mutually reinforcing. In contrast, for me their meeting was a collision that forced me to make a choice. It had to be one story or the other.

I chose the Jesus story to be my defining story—and chose against the American Empire. That choice led me to affirm Christian pacifism and turn from the uncritical nationalism central the Empire story. I started to interpret the story of the American Empire without blinders. At the same time, I found the Bible to be a key source for a peace-oriented, anti-empire defining story. My fundamentalist Christian teachers had asserted a high view of the Bible as direct revelation from God. However, such an assertion had not protected them from uncritical nationalism. Rather than rejecting the Bible when I rejected fundamentalism, I started reading the Bible in a different way. I no longer ignored Jesus’s peace teaching as I had been taught; I made it central.

The basis for stepping away from uncritical nationalism

When I began to read the Bible for peace, I noticed its critique of uncritical nationalism. I noticed the Bible did not teach the submit-to-the-government message as Americans assumed. If the Bible be central, I would choose Jesus’s gospel of peace instead of uncritical nationalism. The Old Testament provides a template, in Torah, that critiques all human territorial kingdoms. Torah pointed to a new kind of kingdom committed to justice and the wellbeing of all its people. The Old Testament kingdom, though, in practice evolved ever more toward injustice, militarism, economic stratification, and corruption. The brokenness grew to a point where the prophets saw the kingdom’s leaders not as agents of God but as enemies of the original vision of a just society.

Eventually, those who retained a commitment to Torah made sustaining those convictions more important than remaining loyal to any kind of territorial kingdom. The story continues with Jesus’s ministry. He announced the presence of God’s kingdom as a non-territorial communal expression of the ways of Torah. Echoing Genesis 12, Jesus’s kingdom message meant to bless all the families of the earth. This blessing would not come through a close connection with territorial kingdoms (or nation-states). Rather, the blessing would come through the witness of countercultural communities that put convictions about the ways of Torah at the center.

Does this story have relevance for our contemporary world? Let me identify four biblical themes that speak to life amidst the world’s empires. (1) The practice of justice should define the aspirations of societies that seek to be healthy. This justice will center on care for the vulnerable of the community since a society cannot be healthy without the good health of those most easily exploited and discarded. (2) People in power should always be treated with skepticism. Power tends to corrupt. People in power tend to be deluded by their commitments to sustain that power at all costs. Such people should be pushed to guide the society toward justice with an expectation that they will likely tend toward serving their own interests and not those of the vulnerable in society. (3) The “horses and chariots” problem tends to define territorial kingdoms and leads to the proclivity to prepare for and engage in warfare (warism). The accumulation of weapons of war favors society’s wealthy and powerful and leads to devastating conflicts. (4) Throughout human history (and in the Bible’s stories), territorial kingdoms and nation-states have provided some of the central rivals to God as the objects of human trust. This type of idolatry, as Israel’s prophets show, leads directly to injustice.

Continue reading “The tragic American Empire story in light of the gospel”