Ted Grimsrud—September 19, 2025

The connection between American Christianity and the preparing for and fighting wars has been long-standing. In this post, I will recount my own somewhat unusual path in navigating this connection. Growing up in the late 1950s and 1960s, I knew little of the wider world. The social and political currents I described in earlier posts certainly shaped the general sensibility of the world I grew up with. However, the impact on me was at most indirect. A key factor for me, in time, proved to be religious faith. Surprisingly, because my family had little religious involvement and my home community would have been considered largely irreligious. Yet….

On the margins of Christianity

I grew up on the margins of Christianity. In my small hometown, Elkton, Oregon, my family attended a tiny Methodist congregation until I was eight years old, when the congregation closed its doors. Our town hosted only one other congregation at that time, a community church. After our Methodist church closed, we would go to Sunday School at that church most weeks.

As a child, I was on my own in terms of faith convictions. I had a lot of curiosity and talked about religion with friends though I do not know why I was so interested. I don’t remember anything from my experience of going to church that ever piqued my interest. I didn’t get challenged by my parents to think about such things. I suspect I had a natural curiosity about the meaning of life and the religious dimension. My interest in God and the big issues intensified as I got older. I had a self-conscious perspective when I entered my teen years inclined to conclude that God did not exist. But it was an open question that I had a keen interest in.

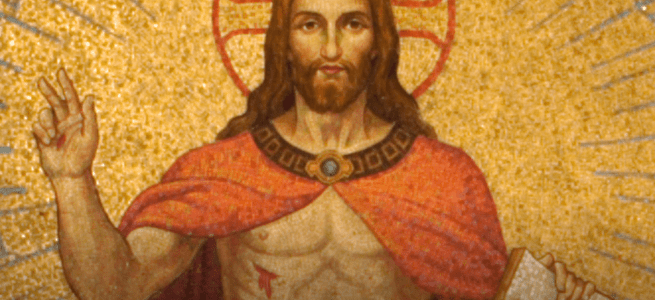

The first move for me came during the Spring of my sophomore year in high school. A friend of mine died of cancer when he was in his twenties. His death left the community grief-stricken. During his funeral, I felt for the first time a strong sense of the presence of God. From then on, I no longer thought of myself as an atheist. About a year later, I started spending time with a somewhat older friend who had became active in a Baptist congregation that had recently started in town. My friend gently engaged me in conversations about faith. He mainly conveyed a general message of God’s love and a simple process to gain salvation. That process mainly involved the seeker praying to God a prayer of repentance for one’s sinfulness and of a desire to trust in Jesus Christ as the savior whose death on the cross opened the path to God’s forgiveness. Finally, one evening in June 1971, I offered the prayer my friend had described to me. I experienced this as a moment of genuine change.